25: And the Band Played On

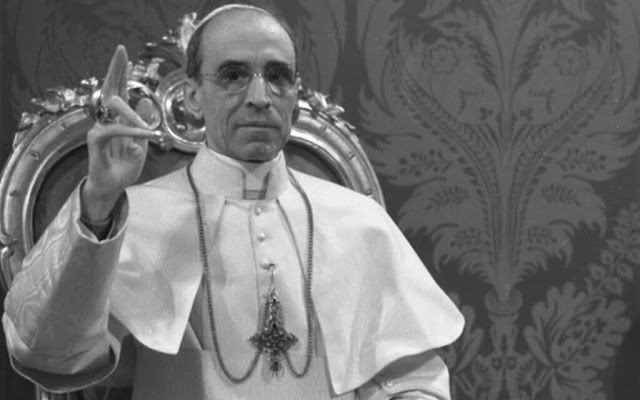

Early in June 1943, Pope Pius XII addressed the Sacred College of Cardinals on the extermination of the Jews. "Every word We address to the competent authority on this subject, and all our public utterances," he said in explanation of his reluctance to express more open condemnation, "have to be carefully weighed and measured by Us in the interests of the victims themselves, lest, contrary to Our intentions, We make their situation worse and harder to bear." He did not add that another reason for proceeding cautiously was that he regarded Bolshevism as a far greater danger than Nazism.

The position of the Holy See was deplorable but it was an offense of omission rather than commission. The Church, under the Pope's guidance, had already saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organization combined, and was presently hiding thousands of Jews in monasteries, convents and Vatican City itself.

The record of the Allies was far more shameful. The British and Americans, despite lofty pronouncements had not only avoided taking any meaningful action but gave sanctuary to few persecuted Jews. The Moscow Declaration of that year -- signed by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin -- methodically listed Hitler's victims as Polish, Italian, French, Dutch, Belgian, Norwegian, Soviet and Cretan. The curious omission of Jews (a policy emulated by the U.S. Office of War Information) was protested vehemently but uselessly by the World Jewish Congress. By the simple expedient of converting the Jews of Poland into Poles, and so on, the Final Solution was lost in the Big Three's general classification of Nazi terrorism.

Contrasting with their reluctance to face the issue of systematic Jewish extermination was the forthrightness and courage of the Danes, who defied German occupation by transporting to Sweden almost every on of their 6,500 Jews; of the Finns, allies of Hitler against the Soviets, who saved all but four of their 4,000 Jews; and of the Japanese who provided refuge in Manchuria for some 5,000 wandering European Jews in recognition of financial aid given by the Jewish firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Company during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

In April 1943, the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Horthy, was summoned by Hitler to Salzburg. Hitler pressed him to deport Hungary's 750,000 Jews to Auschwitz, but Horthy refused. Almost a year later, to prevent Horthy from turning his back on Germany and pulling out of the war, German troops marched into Hungary. By a grim turn of events, the fate of Hungary's Jews at last lay with Germany.

With the Germany troops entering Hungary in March 1944, came an SS unit headed by Adolf Eicmann. He brought a comprehensive deportation plan, devised a few weeks earlier when the SS unit met at Mauthausen concentration camp. Each of the five men devising it were experts on the Final Solution.

The first deportations from Hungary to Auschwitz began on May 15, 1944, with SS units supervising the round-ups. When Jews tried to resist boarding the trains, they were shot down by the SS. The trains were driven by Hungarian railway workers and guarded by armed Hungarian police to the Slovak border. When the Hungarian Jewish leader Rudolf Kastner asked Eichmann for six to eight hundred exemptions to the deportations, Eichmann told him, "You must understand me. I have to clean up the provincial towns of their Jewish garbage. I must take this Jewish muck out of the provinces. I cannot play the role of savior of the Jews."

On May 25, SS General Edmund Veesenmayer, Reich Plenipotentiary and Hitler's deputy in Hungary, reported to Berlin that 138,870 Jews had been deported to their "destination" in the previous ten days. That same day, a group who were being led around Auschwitz-Birkenau's electrified perimeter fence to one of the two gas chambers situated at the far edge of the camp, sensed that something was wrong.

Calling out to each other to run, they scattered into the nearby birch wood. The SS immediately switched on the searchlights installed around the gas chambers, and opened fire with machine guns on the fleeing Jews. There were no survivors. A similar act of revolt took place on May 28, and ended with similar results.

On May 29, more than a thousand Jews reached the German border from the southern Hungarian city of Baja, on route to Auschwitz. They had been sealed in the wagons for three and a half days. At the border the wagons were opened for the first time. Fifty-five Jews were dead, and two hundred had gone mad.

As many as three deportation trains left Hungary every day for more than fifty days. As the weeks passed, fewer and fewer of these deportees were taken as slave laborers when they reached Auschwitz. Of more than a thousand Jews from the town of Bonyhad who were deported in one of the last trains, on July 6, 1944, just over a thousand were murdered. Only seventy survived the war.

On May 15, 1944, a train (Convoy 73) left Paris with 878 Jews locked into its fifteen cattle cars. Unlike previous deportations from Paris, in which men, women and children were deported together, this deportation consisted almost entirely of men. There were also thirty-seven boys between the ages of thirteen and eighteen. One boy, David Gelbart, who was deported with his sixteen-year-old brother Maurice, was two weeks short of his thirteenth birthday -- the day of his barmitzvah, a Jewish boy's coming of adulthood. The youngest deportee, Maurice Gattegno, born in Nice, was twelve.

Almost all of the deportees had been born far from France. Two had been born in London, one in Cuba, two in Jerusalem and one in Baghdad.

All but four of the previous deportation trains from Paris had gone to Auschwitz. Those four had gone to Sobibor. Convoy 73 went much further east, to the former Lithuanian capital, Kovno, more than a thousand miles from Paris. It was believed by the deportees that the call had gone out for a labor battalion in the area towards which Soviet troops were steadily advancing.

Some of those on the train had made special efforts to be included, regarding such labor as a chance of work, shelter, food and survival. One of them, sixteen-year-old Guy Sarner, lied about his age in order to be taken (and was among the few who survived the war). He recalled that several deportees died of thirst during the journey eastward.

Reaching Kovno after three days and three nights, as many as 400 deportees were taken to the Ninth Fort on the outskirts of the city, the scene of the massacre of tens of thousands of Kovno Jews two and a half years earlier. Inside the fort, they were kept in prison cells. Dozens of them carved their names into the walls. One of them, determined to record their plight, wrote: Nous sommes 900 Francais (We are 900 Frenchmen). One of the deportess, Israel Kopelov, had been born in Kovno thirty-eight years earlier.

Most of the Ninth Fort prisoners from Paris were taken to a slave labor camp at Pravieniskes, twelve miles from Kovno. Many were executed there by Lithuanian auxiliaries, on SS orders.

Four hundred of the deportees from Convoy 73 were taken by rail north-eastward from Kovno, another five hundred miles to the former Estonian capital, Reval. During the journey there were more deaths from thirst. Six days after their arrival in Reval, sixty of the deportees were taken away, allegedly for work, but were never seen again. The rest were made to work on airfield repairs.

On July 14 -- France's national holiday -- sixty of the Paris deportees then in Reval were taken to a nearby forest and shot. A month later, on August 14, a further hundred, whom their German guards judged too sick to work, were sent southward to an "unknown destination" and killed. The rest were sent to Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig, where many died.

From Convoy 73, only twenty-three of the 878 deportees survived the war.

The Kovno ghetto was divided into a Small and Large Ghetto, separated by a footbridge. A Jewish Council sought to regulate life as normally as possible, and a Jewish police force kept order. A distinguished physician, Dr. Elchanan Elkes, became head of the Council, and he worked tirelessly to mitigate the hardships of ghetto life.

On October 4, 1941, the Germans surrounded the Jewish contagious disease hospital, locked the doors, barred the windows and set the building on fire. All sixty-two people who were there at the time, including a doctor and two nurses, were killed. That day, the patients in the ghetto's General Hospital and inhabitants of the Small Ghetto, were taken to the Ninth Fort and killed.

On October 28, the senior SS officer in Kovno, Helmut Rauca, ordered all the ghetto inmates to Democracy Square. There, during the course of a whole day -- in what was known as the "Great Action" -- he selected 10,000 Jews, all of whom were sent to the Small Ghetto for twenty-four hours, and then to the Ninth Fort, where they were killed. By December 1942, only 16,000 Jews were still alive in the ghetto -- 19,000 had been killed.

The Kovno ghetto -- like Warsaw until the uprising of 1943, like the Lodz ghetto until the final deportations of 1944 -- relied for its survival on work done for the German-run factories in the ghetto workshops, which employed 2,000 Jews, and at the nearby airport, a transit point from Germany to the Russian front, where 8,000 Jews were employed. Those 10,000 who had work permits, also had rations on which they and their families could survive. Those without work were in danger of starvation, arrest and execution.

The Jewish Council made strenuous efforts to ameliorate hunger and hardship, feeding 2,000 Jews, mainly women and children, of whom the Germans were told nothing. Had they known about them, they would have been sent to the Ninth Fort. The Council also organized cultural events, concerts, debates, lectures and sports activities in an attempt to maintain morale. Religious and Zionist gatherings took place. A physician, Dr. Moses Brauns, organized a medical system that had as its prime task the control of contagious diseases, lest the Germans used the excuse of disease to destroy the ghetto altogether.

Deportations from Kovno to slave labor camps in Estonia began on October 26, 1943. That day, the first train with children and old people locked into its wagons was sent to Auschwitz. Then the "status" of the Kovno ghetto was officially changed and it became a concentration camp. The chance of "living through" the German occupation was dwindling. On December 25, 1943, however, sixty-four slave laborers escaped from the Ninth Fort.

In March 1944, after a tenacious German search, 1,200 Jews in hiding -- those of whom the Germans had earlier known nothing -- were found killed. Fewer than a hundred remained in hiding. Between July 8 and 11, 1944, as Soviet forces approached Kovno, the surviving 8,000 Jews still working in the ghetto were sent westward, the women to Stutthof, the men to Dachau. Dr Elkes died in Dachau. Dr. Brauns survived.

An estimated 200 Jewish children from Kovno survived the war, hidden by Lithuanians in the city and in the nearby countryside.

Comments

Post a Comment